Aband of light, reflected across the waters of Morgan Lake, New Mexico, leads our eyes from the centre foreground to a power plant on the Navajo Reservation: the Four Corners Power Plant, one of the largest coal-fired generating stations in the United States. In this photograph by the Diné artist Will Wilson, the plant is entirely in shadow, as dark as the bituminous coal that fuels it. Morgan Lake is an artificial formation, built in 1963 to serve as a cooling pond for the plant, its water constantly replenished by the San Juan River.

Light is reserved for the three rectangular waste ponds to the left, for the scar of the surface mine behind the plant and for the smoke carrying ‘atmospheric depositions of mercury’ onto the Navajo Nation’s land, and into its animals, people and water. The dark line of coal refuse mimics the hills and mesas, forming an intermediate horizon which cradles the power station. Dark blue shadows of waste extend across the photograph just as their contaminants spread into human and non-human communities and seep into the groundwater. Towards the horizon stands the sacred Shiprock, with the Chuska Mountains behind. The vegetation is brown; roads, the edges of ponds and the railway from the mine to the power station are scored into the landscape, razor sharp.

The Morgan Lake seen in New Mexico tourist brochures and on websites is a tempting cobalt blue, offering windsurfing, boating and fishing in water that is pleasantly warm all year round. Wilson tells a different story. In another photograph, the aquatic environment has a palette of mineral grey, evoking the hidden dangers to humans and wildlife – aluminium particles, mercury, selenium and more. Swimming in the lake is banned. A forbidding presence saturated in blue-grey, the power station seems to emerge from the mounds of toxic coal refuse which leach iron and manganese residues. A weighty imposition on the landscape, an aberration rather than an integral part of it, the steel, concrete and brick of the plant contrast with the fringe of sagebrush and piñon pine along the shoreline, stubbornly clinging to life. The sky is washed with grey against the light. Its colour suggests pollution, the emission of nitrogen oxides and sulphur dioxide.

In the bottom third of the image the chimneys are reflected in the water, the solidity of the power plant dissolving into grey streaks and ripples of movement. Can we imagine its disappearance, as we must imagine the disappearance of all coal-fired power plants? The foreground provides the only warm colours in the photograph: a few splotches of madder brown and the sienna of grasses blowing in the wind. The warmth of these colours speaks to life: here on the bank nearer the viewer is the alternative meaning of ‘plant’, life generated rather than extinguished in a process the academic Rob Nixon has described as ‘slow violence’.

Whiteness, seen from a distance. Fifty shades of whiteness, according to the title. Whiteness as ubiquitous and banal, its excess evident in the seepage beyond the black borders of the US. Jaune Quick-To-See Smith’s crafty layering in Fifty Shades of White echoes the creation of this elaborate fiction, a fiction that continues to exercise an extraordinary, destructive power. I am reminded of the first maps I saw as a child, hanging on the walls of British classrooms. Of course, the colour that occurred most often on those maps was red, not white, a difference in surface but not in substance: that red and the white on this map signal the same thing – a celebration of power and domination. Smith is a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes; her maps portray ‘stolen lands’. Black paint outlines what would be recognisable to many as the United States of America, bordered by Canadian provinces to the north, the states of Mexico to the south and, in the Caribbean, by Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, painted in solid colours: red, blue, orange and yellow.

The names that are today allocated to American states are absent, erased. In their place, Smith has inserted typeset labels with names suggestive of paint colours. They are wry and make me laugh. In what is now New England, where I live, Massachusetts is ‘True White’; New Hampshire, ‘Pure White’; Vermont, ‘Extra White’; and Maine ‘Ultra White’. Pennsylvania is, of course, ‘Antique White’. Georgia is ‘White Peach’ and Florida ‘White Grapefruit’.

Smith has also pasted on typeset extracts from newspapers and overheard remarks. The label on Kansas (renamed ‘White Corn’) reads: ‘Native Americans are those unrecognisable peoples who look Italian, Asian or Greek and everyone says, “But you don’t look Indian to me. I know because I’ve seen Indians in the movies.”’ On ‘Glamorous White’ (California) is a related comment: ‘American Indians in Hollywood movies come from Greece, Italy, Turkey, Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Romania, Spain, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Kazakhstan, Tunisia, Libya, Mauritania, Israel and Palestine.’ Over Majestic Mountain (Montana), Smith’s homeland, is this note: ‘When the US government forbade tribes from dancing drumming and singing, the Salish decided to celebrate the nation’s birthday on the Fourth of July by dancing drumming and singing. The government found no way to say no to honouring the US.’ There is no beauty here. But we notice that the whites and creams fail in their attempt to obliterate the many shades of brown and black beneath.

In another painting, State Names, Smith says that she ‘erased all European presence’, keeping ‘only the states that have Native American names because this whole place was ours until the invasion came’. Arbitrary colonial boundaries, boundaries that fail to acknowledge indigenous sovereignty, are obscured by running, bleeding, dripping paint. It takes work to uncover not only what is present, but what is missing or obscured. The only names that remain visible are those that originate from one of the Indigenous language groups – Wisconsin, Kentucky and Massachusetts, for example. Borders, including those between Canada, the US and Mexico, disappear under the liquid blues and greens.

In recent work, Smith has dislodged the North American landmass, turning it 90° anticlockwise. In several paintings from 2021, she surrounds her maps with basketry and beadwork designs from the Plateau region, which spans the border between what’s now the northwest United States and British Columbia. She describes the disorientation of making these maps. Freed from the familiar map, and ‘totally surrounded by Native design’, the landmass became unfamiliar, even dangerous. Stolen Map contains an explicit reference to the cartography it subverts: ‘Maps have been the weapons of imperialism’ – a quotation from The New Nature of Maps by J. Brian Harley.

Smoke Signals Map attempts to capture colonisation through the air – in the products of pollution and the huge fires associated with climate change. ‘Climate Change is giving us Smoke Signals’ reads a label in the centre of the picture. The double meaning of ‘smoke signals’ points to our complacency. Smoke from a power plant chimney is not heeded as a warning, yet it kills as surely as any fire. Another label printed on the picture reads ‘MANIFEST DESTINY ONWARD TO MARS’, denouncing the hubris of Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson and Elon Musk, with their desire to colonise the sky above us, other planets, space itself. Smith’s dislodged landmass is almost awash in coastal flooding: entire states (Texas, Florida, Maine, Connecticut, Massachusetts) and swathes of the northwest are inundated with water. The area of dark red paint indicates not smoke but a different type of toxic air – the largest methane gas cloud in North America, as measured by the European Space Agency. Methane is an odourless and colourless gas that can be seen only by infrared cameras. ‘Yellows and red indicate higher-than-normal anomalies, with more intense colours showing higher concentrations. The Four Corners area – the area where Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah meet – is the only red spot on the map,’ Nasa commented of the European Space Agency’s findings.

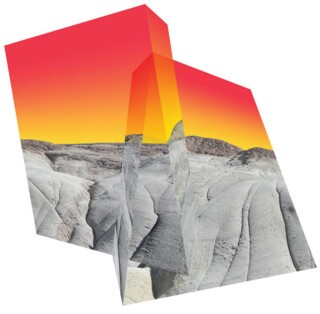

In the photograph Altered Landscape 1 (2019), the Tewa/Hopi artist Michael Namingha uses yellows and reds to make visible the methane cloud over the Navajo Nation. His Altered Landscape series consists of abstract works in which geometric shapes in neon colours are juxtaposed against black and white aerial landscapes from the Four Corners region. His compositions are mounted on shaped plexiglass and are two-dimensional but create the illusion of being three-dimensional. Namingha wants us to move around his images as we would around a piece of sculpture and to note where they appear to expand or contract.

The term ‘Indigenous Futurism’ is sometimes used to characterise those works by Indigenous artists that upend the dichotomy of traditional v. modern. As Wilson puts it, ‘people don’t usually think of Native folks … and then the future in the same breath.’ A younger generation of Indigenous artists, the students he teaches, talk about their work as ‘remembering the future’. Indigenous language and design is not consigned to the past but provides the means of understanding – and perhaps reimagining – a threatening future. He uses the phrase ‘trans-customary’ in a similar fashion: ‘Work that we make today … is informed by a tradition, but tradition is ever evolving … you can have both traditional and contemporary influences informing one another.’ He is alert to the ways photography has been used as a mechanism of colonisation, and seeks to indigenise the form, practice and process of the medium.

In 2013, the Denver Art Museum exhibited Wilson’s Auto Immune Response: Weaving the Sacred Mountains, which consists of four individual beaded panels or ‘weavings’. This forms part of his multimedia Auto Immune Response project, or AIR (2004-21), ‘an allegorical investigation into the extraordinarily rapid transformation of Indigenous lifeways, the dis-ease it has caused and strategies of response that enable cultural survival’. The four beadwork panels symbolise the four sacred mountains of the Diné Bikéyah, the sacred and ancestral homeland of the Navajo nation. Embedded in the beadwork are QR codes, which take the viewer to a video of the AIR protagonist (a version of Wilson himself) in the landscape represented by the weaving.

Auto Immune Response comprises more than 65 artworks, all located within the Dinétah – the ancestral homelands of the Diné in the Four Corners region – and the Navajo Nation. In the 1930s federal incursions into Diné life and land increased rapidly. Navajo land was extensively surveyed and mapped by various arms of the federal government. The US Soil Conservation Service determined that the land which had long sustained the Diné and their livestock was unsuitable as pasture and instituted a stock reduction programme, forcibly slaughtering hundreds of thousands of sheep. The land was reclassified as ‘materially and ideologically suited for extractive industrialism’. Mineral, oil and mining surveys escalated. Surveyors, prospectors, mine operators and millers invaded Diné Bikéyah. The region became the battery powering cities in Arizona, California and Nevada, the source of power for the Cold War weapons industry and for commercial nuclear power: in short, it became central to the nuclear industrial complex.

The legacy has been death and disease. Uranium mining and processing, nuclear weapons production facilities and atomic test sites leave irradiated landscapes. As mines, mills, nuclear facilities and weapons production sites have been abandoned, the scale of contamination has become clear. Radioactive and toxic waste is too expensive to clean up. As early as 1988, engineers at the US Department of Energy were using the term ‘national sacrifice zones’ without referring to who or what was to be sacrificed. There are more than five hundred abandoned uranium mines in the Navajo Nation alone.

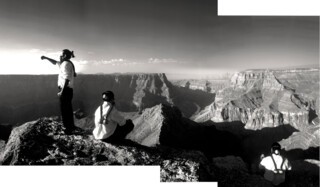

Like Smith, Wilson offers an alternative cartography. AIR 2 upsets familiar representations of the Grand Canyon, not only because the three figures are wearing breathing apparatus, but also because, as Wilson describes, they are looking over the ‘confluence of Little Colorado and Colorado Rivers … from the Navajo Nation side of Grand Canyon … a perspective that not a lot of people see, because it is remote and you have to travel through Navajo land to get there’. To Wilson this landscape is deeply familiar: this site represents home, family, a relationship to the land over multiple generations; it is close to where his family had their winter sheep camp.

Dates like 16 July 1945, 6 August 1945, 9 August 1945 haunt the first photograph in the Auto Immune Response series. They represent the bitter extreme of Western imperialism, settler colonialism and racial capitalism: the profound disregard for human and non-human life; the willingness to embrace mass death and devastating environmental destruction. As Achille Mbembe writes, ‘in its dank underbelly, modernity has been an interminable war on life.’ These dates also augured a new future: a massive increase in the rate of resource extraction and the beginning of the nuclear age of weaponry and energy production during which the federal government and mining companies turned the Diné into exploitable and expendable labouring bodies: in short, waste.

AIR 1 is an inkjet print with the proportions of a mural: the original measures almost three metres in length. This landscape seems a vast ominous expanse, eerie in atmosphere, apocalyptic in scale, segmented by a barbed-wire fence that marks the horizon. At the left side Wilson has overlaid an image of the Trinity explosion – the first ever detonation of a nuclear weapon, in New Mexico on 16 July 1945 – which rises and, in reflection on a liquid surface, descends through light on either side of the horizon. Other cloud towers and their reflections are visible to the right, forms that resemble or echo those that rose over Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945.

Wilson places himself in the series as the Diné man described only as ‘the protagonist’: a post-apocalyptic Navajo man, a survivor who travels through empty landscapes of detritus and decay. The protagonist appears twice in AIR 1. In the foreground, we see him in profile – this is the only image in the series where he is without mask and breathing apparatus. He is superimposed against and set apart from the landscape. His hair is tied back in a traditional tsiiyéél. His determined expression suggests the enormity of the project ahead, a consideration of the questions that will propel him into multiple roles: time traveller, explorer, scientist, hero and potential healer. But the viewer has only questions. Where has everyone gone? What cataclysm has transformed the familiar and strange landscape? Why has the land become toxic to him? How will he respond, survive, reconnect to the earth? He appears again as if part of the fence, beginning his journey and now wearing the life-sustaining breathing apparatus. His right arm is lifted in a Diné gesture of sprinkling pollen, a ritual of blessing and healing.

It was clear by 1970 that the uranium industry was producing a deadly epidemic of cancer and other radiation-related diseases, which weren’t just affecting the people who worked in the mines and mills. Radioactive geographies have proved difficult to map, whether at the scale of Diné Bikéyah or at more local levels, with the risk of toxic contamination from tailings moving with the rain, wind and animals. Pollutants infiltrate homes and bodies. Uranium has a half-life of 4.5 billion years: how do we begin to represent such timescales? These are the difficulties that animate Wilson’s project. His title suggests not only the immune system of the human body, which attacks itself as it tries to cope with particles to which it should never have been exposed, but also the way environmental pollution is causing an auto-immune response in the planet itself.

In AIR 5 the protagonist is doubled, a reference to the Hero Twins of the Navajo creation story. Two heads turned away from each other, two sets of bloodshot eyes looking out accusingly, implicating the viewer. Who will accept responsibility? The tubes of their breathing apparatus seem to curl and flap uselessly, attached, or so it appears, only to each other’s masks. There are no oxygen tanks. Are they breathing each other’s exhalations? Hair, faces, clothes and masks are covered in what we imagine to be radioactive dust. Are we looking at humans who have been rendered disposable, waste, against a liquid, leached out, contaminated landscape? Are we looking at a death sentence, planetary death in a palette of red, white and blue? They demand recognition, a witnessing, a reckoning.

The latest iteration of AIR features an installation of a greenhouse in which indigenous food plants are being grown. Having focused so far on the toxic legacy of uranium extraction on Dinétah, Wilson is now collaborating with the University of Utah’s Red Butte Garden to turn his steel hogan – the traditional home of the Navajo people – into a greenhouse for growing local plants that remove heavy metals and toxins from the soil. Plants undoing the work of our plants.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.